title

The Senster

artist

Edward Ihnatowicz

intro

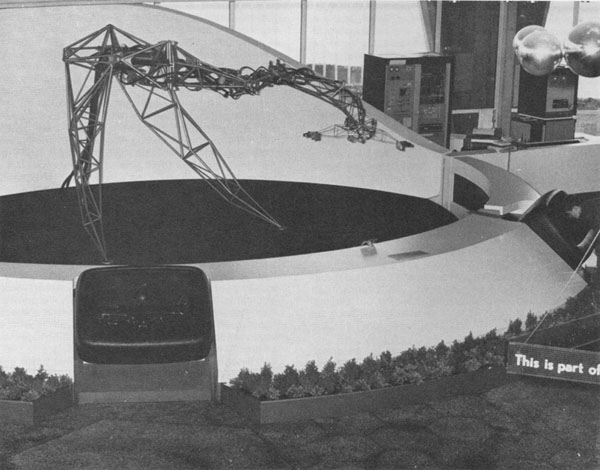

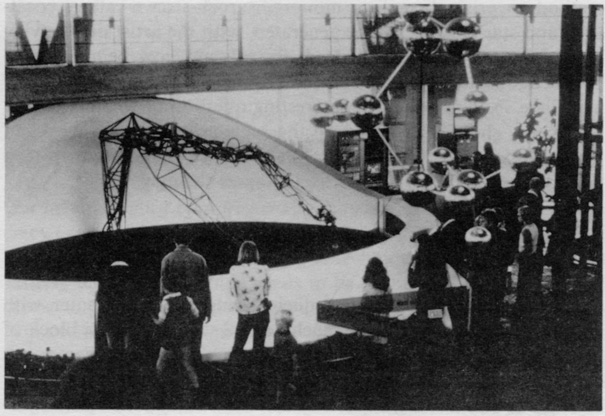

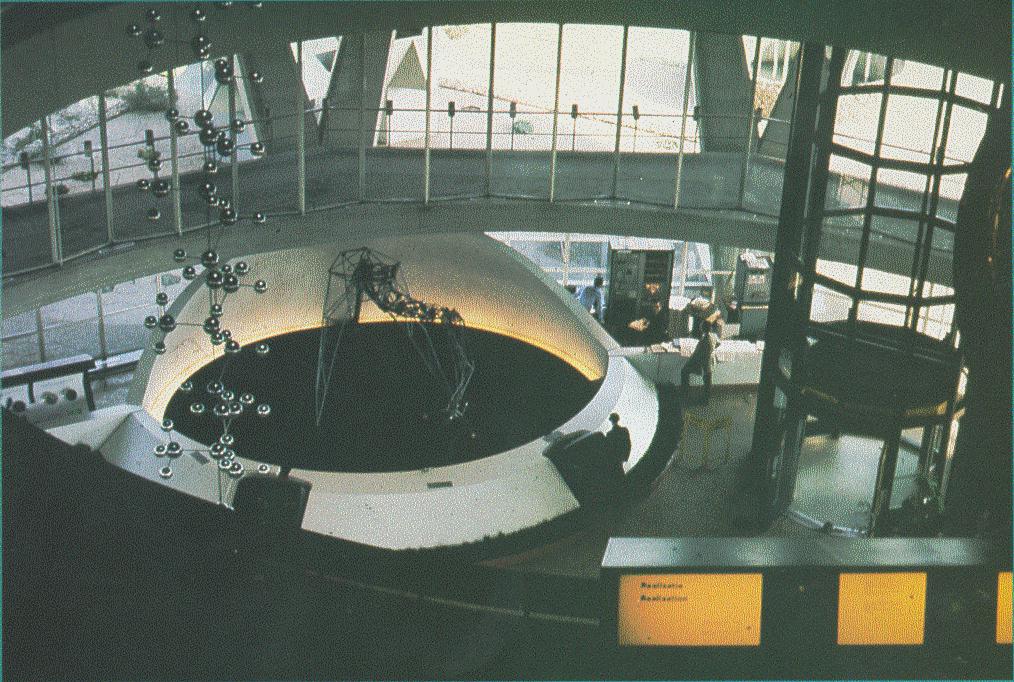

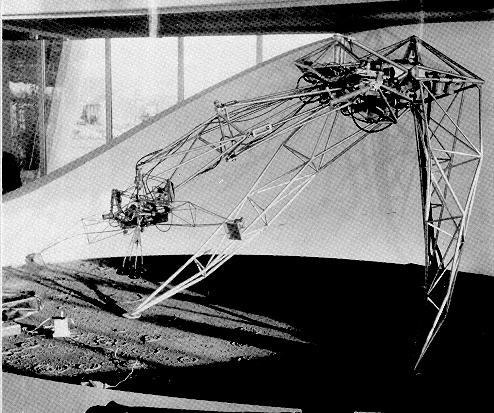

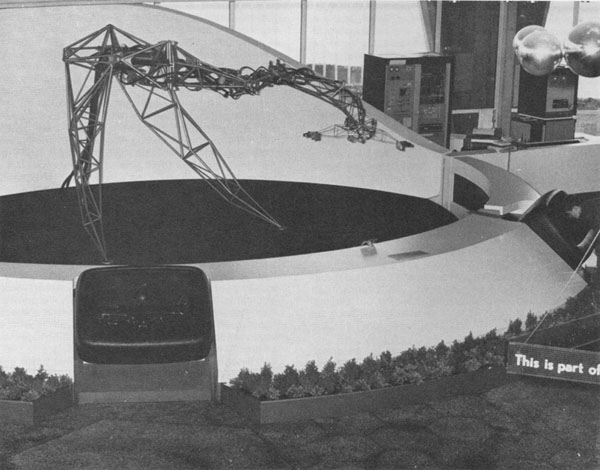

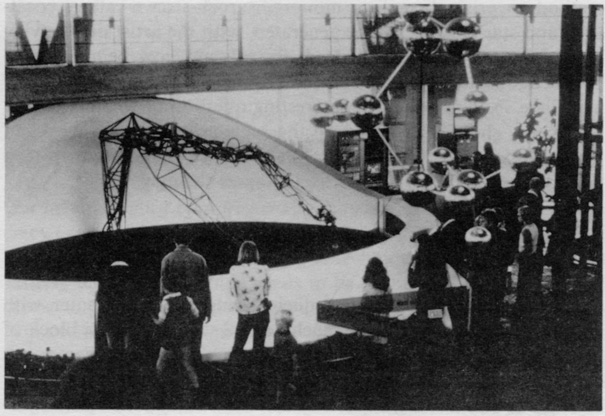

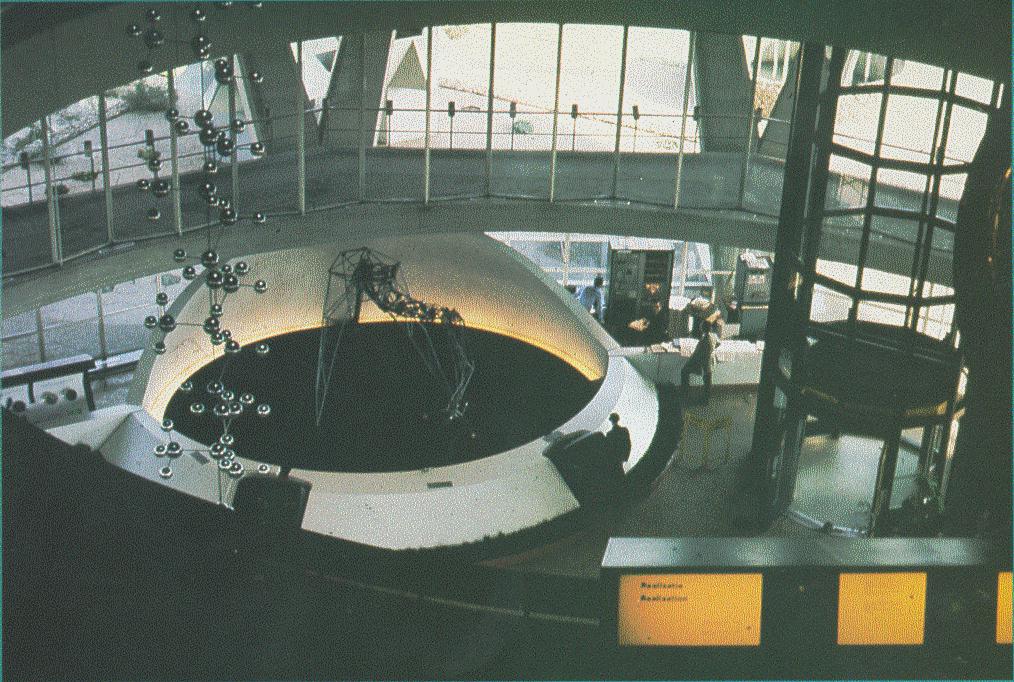

The Senster was a 4 meter tall robot, commissioned by Dutch electronics manufacturer Philips to be on show at the Evoluon, its exhibition space dedicated to science and technology in Eindhoven. It was one of the first computer controlled robotic works of art and could be visited between 1970-1974 in the entrance hall gallery of the Evoluon.

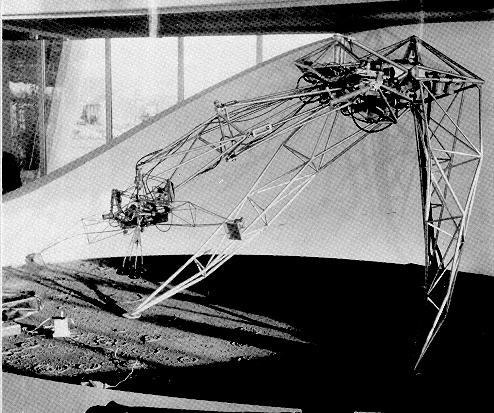

The work consisted of a steel skeleton, with a resemblance to a dinosaur or a giraffe with its long neck. The ‘beast’ reacted to sound and movement made by the visitors. Its two legs remained immobile and connected to the ground, but its neck and head moved and could follow people around the room.There were three different movement responses built into the robot: gentle sounds would make its head move toward the visitor, loud sounds would make the head pull back, and when a visitor performed fast movements the robot would follow these. Spectators reacted with great enthusiasm to the robot. Apparently people would wave, shout, and throw things at it.

In 1974 Philips decided to dismantle the work. The skeleton remained on display in the open-air in Zeeland for over 40 years and was acquired and shipped to Poland in 2017, where the University of Science and Technology in Krakow organized a project focused on reviving the work.

biography artist

Edward Ihnatowicz (1926 -1988) was a cybernetic sculptor who explored interactivity between his robotic works and the audience. Born in Poland in 1926, Ihnatowicz was a war refugee in Romania and Algeria between 1939-1943. In 1943 he arrived in the UK where he studied at the Ruskin School of Art (Oxford) between 1945 and 1949. During this period he mainly focused on furniture and interior design. In 1962 he went to Poland, where he lived in a garage and started experimenting with living sculpture.

In 1968 his interactive sculptures were featured in the exhibition “Cybernetic Serendipity” in London and the US. Between 1971-1986 he worked as a Research Assistant in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at University College, London.

keywords

robot, robotica, sculpture, installation, electronic art, sensor, cybernetic

images

[caption id="attachment_1046" align="alignnone" width="600"] Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (4)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1047" align="alignnone" width="491"]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (4)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1047" align="alignnone" width="491"] Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (3)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1048" align="alignnone" width="605"]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (3)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1048" align="alignnone" width="605"] Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (2)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1049" align="alignnone" width="1014"]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (2)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1049" align="alignnone" width="1014"] Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (1)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1050" align="alignnone" width="494"]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (1)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1050" align="alignnone" width="494"] Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate[/caption]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate[/caption]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (4)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1047" align="alignnone" width="491"]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (4)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1047" align="alignnone" width="491"] Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (3)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1048" align="alignnone" width="605"]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (3)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1048" align="alignnone" width="605"] Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (2)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1049" align="alignnone" width="1014"]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (2)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1049" align="alignnone" width="1014"] Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (1)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1050" align="alignnone" width="494"]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate (1)[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_1050" align="alignnone" width="494"] Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate[/caption]

Edward Ihnatowicz, The Senster, 1970. Photo from the Ihnatowicz estate[/caption]

year

1968-1970

website

A great resource is the website by Senster fan Alex Zivanovic: senster.com.

This website is about a project on rebuilding The Senster by the AGH University of Science and Technology in Krakow: senster.agh.edu.pl.

This website about the Evoluon, run by Kees Stravers, offers info about The Senster and some recently discovered parts of the work from the time of its exhibition in the Evoluon in the early ‘70s: dse.nl/~evoluon.

premiere

The work was commissioned in 1970 by Philips to be put on display from 1970 to 1974 at the Evoluon (Eindhoven, The Netherlands). It was unveiled at Evoluon in September 1970.

software

The interaction sequence within the work was regulated by a program written in Assembler and encoded into a Philips P9201 prototype computer. On this website, Alex Zivanovic offers an (almost) complete listing of the surviving source code of The Senster: senster.com.

functionality

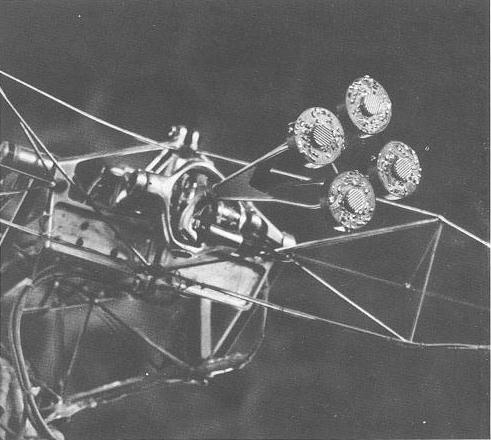

The Senster was an interactive hydraulic robotic sculpture, controlled by a digital computer. Various sensors were placed in the robot’s ‘eyes’ and ‘head’, and responded to the sound and movement of the audience.

part of collection

In April 2017, the work was acquired from the private collection of Dutch-based company Delmeco Group by the AGH University of Science and Technology (Krakow, Poland).

production

For the creation of the mechanical structure, Ihnatowicz made rough sketches that he presented to a technician at the Thermodynamics sub-basement of the Mechanical Engineering Department of University College London.The technician, whose name was Stan (last name unknown), constructed the skeleton.

The welding of the mechanical structure was outsourced to a Dutch company called Verburg Holland. When the work was dismantled in 1974 at Evoluon, Verburg Holland decided to take the skeleton and install it outside next to their office building in Zeeland. In April 2017, the skeleton was acquired from its owner, Delmeco Group, by the AGH University of Science and Technology (Krakow, Poland). A lorry came to pick-up the skeleton, and it travelled to Krakow where the work was reactivated within the project Re:SENSTER (for the full project description see: senster.agh.edu.pl). For the full story, see vimeo.com.

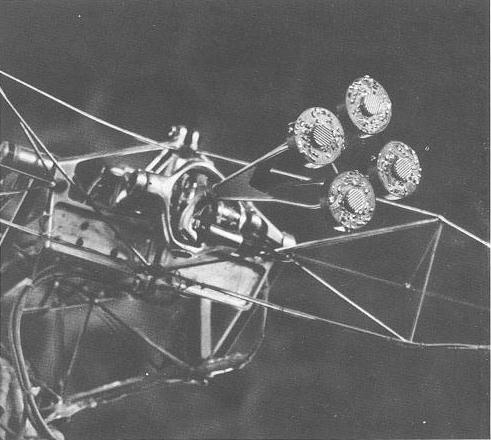

The skeleton was fitted with various sensors for sound and movement. In its ‘head’, an array of microphones and a Doppler radar system was placed. The joints of the skeleton were powered by hydraulics.

The code for the interactivity sequence was written by Ihnatowicz himself with the help of Peter Lundahl, a sysadmin at Evoluon. Lundahl also added refinements to the software after Ihnatowicz left at the end of 1970.

Originally, the computer that controlled the robot was programmed to react to loud sounds. However, as this provoked a cacophony of sounds whenever school groups visited, Ihnatowicz reprogrammed the robot, upon Philips’ request, to respond to more gentle noises and movements.1 Finally, the mechanism reacted to moderate and low sounds, loud sounds, and fast motion.

hardware

The control system consisted of a computer and a hydraulic modulator. Computer specs: Philips P9201, which was a copy of the more well-known Honeywell DDP-416. It was a 16-bit computer with an 8K core memory and paper tape for the external memory. No original models are left anywhere in the world of this computer.

technical specs

Philips P9201 computer, 4 microphones, 2 Doppler radar sensors (original type: HP module type 35200B/001), mounted in the eyes of The Senster with custom made antennae. This system worked on 10 GHz.

intention artistquote by artist

quote

“Ihnatowicz’s interest in kinetics stemmed from his conviction that the behaviour of something tells us far more about it than its appearance. This led him to build the Senster, one of the most influential kinetic sculptures ever made.”2

influence

context

Benthall, Jonathan. Science and Technology in Art Today: with 95 Illustrations. Thames and Hudson, 1972.

Brown, Paul. “The Idea Becomes a Machine AI and A-Life in Early British Computer Arts.” Engineering Nature: Art & Consciousness in the Post-biological Era. edited by Roy Ascott, Intellect, 2006.

Kac, Eduardo."Origin and Development of Robotic Art." Art Journal, edited by Johanna Drucker, vol. 56, no. 3, Digital Reflections: The Dialogue of Art and Technology, 1997, pp. 60–67.

Michie, Donald, and Rory Johnston. The Creative Computer: Machine Intelligence and Human Knowledge. Penguin Books, 1984.

Reichardt, Jasia. "Art at large." New Scientist. 4 May 1972.

Reichardt, Jasia. Robots: Fact, Fiction, and Prediction. Thames & Hudson Ltd., 1978.

Simons, Geoff. Are Computers Alive? Harvester, 1983.

Zivanovic, Aleksandar. “The Development of a Cybernetic Sculptor: Edward Ihnatowicz and The Senster.” Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Creativity & Cognition , 2005, pp. 586–591.

Zivanovic, Aleksandar. "SAM, The Senster and The Bandit: Early Cybernetic Sculptures by Edward Ihnatowicz." Robotics, Mechatronics and Animatronics in the Creative and Entertainment Industries and Arts Symposium, AISB 2005 Convention, 13 April 2005.

LITERATURE

part of active discussion

Around 2009, The Senster was apparently rebuilt by a group of students from Utrecht University (The Netherlands) in a project named “Senster Revived”. However, other than a dead link in the Evoluon website dse.nl/~evoluon), more information about this project seems to be unavailable.

Also see Alex Zivanovic’s “Curating a history of Computer Art: the work of Edward Ihnatowicz”, which addresses ethical questions concerning the artwork and its afterlife.3

scene artists institutes

Philips

footnote

1 Paul Brown, “The Idea Becomes a Machine AI and A-Life in Early British Computer Arts.” Engineering Nature: Art & Consciousness in the Post-biological Era. edited by Roy Ascott, Intellect, 2006, pp. 230.

2 Ruairi Glynn, “Edward Ihnatowicz – The Senster.” Interactive Architecture Lab, 15 Jan. 2008, interactivearchitecture.org.

3 Alex Zivanovic, “Curating a history of Computer Art: the work of Edward Ihnatowicz.” idc.cs.mdx.ac.uk (pdf).

Annie Abrahams

Livinus van de Bundt & Jeep van de Bundt

Driessens & Verstappen (Erwin Driessens and Maria Verstappen)

Yvonne le Grand

Edward Ihnatowicz

JODI (Joan Heemskerk & Dirk Paesmans)

Bas van Koolwijk

Lancel/Maat (Karen Lancel and Hermen Maat)

Jan Robert Leegte

Peter Luining

Martine Neddam

Marnix de Nijs and Edwin van der Heide

Dick Raaijmakers

Joost Rekveld

Remko Scha

Jeffrey Shaw

Debra Solomon

Steina

Peter Struycken

Michel Waisvisz